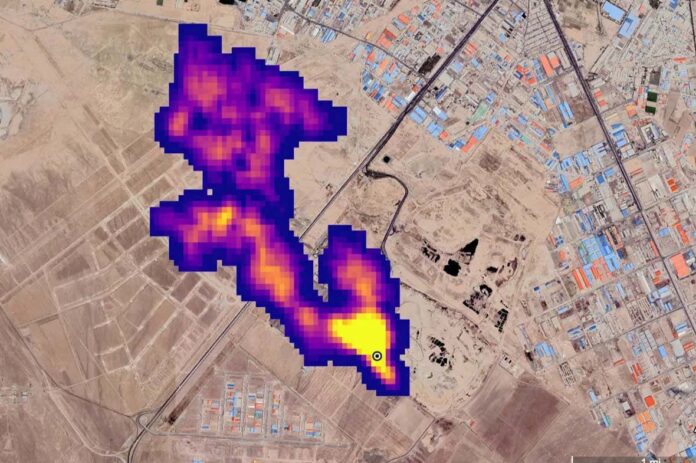

A methane plume at least 4.8 kilometres long billows into the atmosphere south of Tehran, Iran

NASA/JPL-Caltech

The world has more ways than ever to spot the invisible methane emissions responsible for a third of global warming so far. But according to a report released at the COP29 climate summit, methane “super-emitters” rarely take action when alerted that they are leaking large amounts of the potent greenhouse gas.

“We’re not seeing the transparency and the sense of urgency that we require,” says Manfredi Caltagirone, director of the United Nations Environment Programme’s International Methane Emissions Observatory, which recently launched a system that uses satellite data to alert methane emitters about leaks.

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas to address, behind carbon dioxide, and a rising number of countries have promised to slash methane emissions in order to avoid near-term warming. At last year’s COP28 climate summit, many of the world’s largest oil and gas companies also pledged to “eliminate” methane emissions from their operations.

Today, a growing number of satellites are beginning to detect methane leaks from the biggest sources of such emissions: oil and gas infrastructure, coal mines, landfill and agriculture. That data is critical to holding emitters to account, says Mark Brownstein at the Environmental Defense Fund, an environmental advocacy group that recently launched its own methane-sensing satellite. “But data by itself doesn’t solve the problem,” he says.

The first year of the UN methane alert system illustrates the yawning gap between data and action. Over the past year, the programme issued 1225 alerts to governments and companies when it identified plumes of methane from oil and gas infrastructure large enough to be detected from space. It now reports that emitters only took steps to control those leaks 15 times, a response rate of about 1 per cent.

There are a number of possible reasons for this, says Caltagirone. Emitters might lack technical or financial resources and some sources of methane can be difficult to cut off, although emissions from oil and gas infrastructure are widely seen to be the easiest to deal with. “It’s plumbing. It’s not rocket science,” he says.

Another explanation might be that emitters are still getting used to the new alert system. However, other methane monitors have reported a similar lack of response. “Our success rate is not much better,” says Jean-Francois Gauthier at GHGSat, a Canadian company that has issued similar satellite alerts for years. “It’s on the order of 2 or 3 per cent.”

Methane super-emitter plumes detected in 2021

ESA/SRON

There have been some successes. For instance, the UN issued several alerts this year to the Algerian government about a methane source that had been continuously leaking since at least 1999, with a global warming effect equivalent to half a million cars driven for a year. By October, satellite data showed it had disappeared.

But the overall picture suggests monitoring isn’t yet translating into emission reductions. “Simply showing methane plumes is not enough to generate action,” says Rob Jackson at Stanford University in California. A core problem he sees is that satellites rarely reveal who owns the leaky pipeline or the methane-emitting well, making accountability difficult.

Methane is a major topic of discussion at the COP29 meeting, now under way in Baku, Azerbaijan. A summit this week on “non-CO2 greenhouse gases”, convened by the US and China, saw countries announce several actions on methane emissions. They include a fee on methane in the US, which is aimed at oil and gas emitters – although many expect the incoming Trump administration to undo that rule.