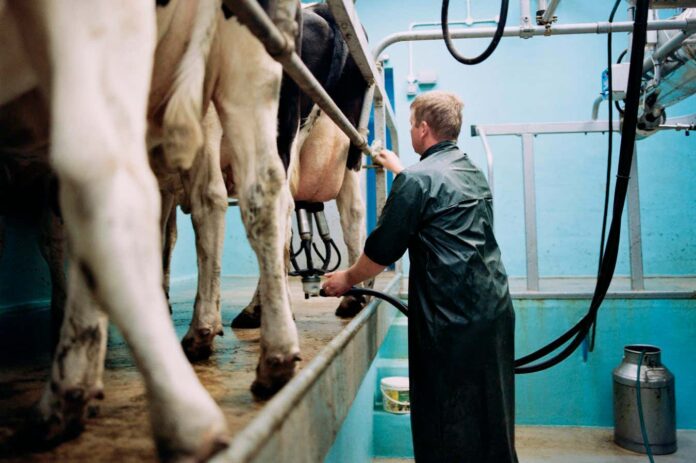

Farm workers exposed to infected dairy cattle have been found to carry bird flu antibodies

Helen King/Getty Images

There may be more bird flu cases in humans in the US than we previously thought. Health departments in two states took blood tests of workers on dairy farms known to have hosted infected cattle and found that about 7 per cent of them have antibodies for the disease. This included people who never experienced any flu symptoms.

Since March, a bird flu virus known as H5N1 has been circulating in dairy cows across the US. So far, 446 cows in 15 US states have tested positive for the virus. Since April, 44 people in the US have tested positive for H5 – the influenza subtype that includes H5N1. All but one of these cases occurred in workers on H5N1-infected poultry or dairy farms.

To better understand how many farm workers may have contracted the virus, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collaborated with state health departments in Colorado and Michigan to collect blood samples from 115 people working on dairy farms with H5N1-infected cattle. All of the samples were obtained between 15 and 19 days after cows on the farms had tested positive for the virus.

Nirav Shah at the CDC and his colleagues then removed seasonal influenza antibodies from the samples before testing them for the presence of H5N1 antibodies. They found H5N1 antibodies in eight of the samples, or about 7 per cent, suggesting that eight of the workers had been unknowingly infected with the virus. What’s more, four of the workers didn’t recall ever having symptoms.

“This is critical because, before this point, the recommendations for [H5N1] testing largely have focused on symptomatic workers,” says Meghan Davis at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland. “When workers don’t know that they are infected, they inadvertently may expose other people in their communities to the infection.”

H5N1 is poorly adapted to infecting humans and isn’t known to transmit between people. Still, more than 900 people globally are reported to have had the virus since 2003, roughly half of whom died from it. Each of these infections offers the virus an opportunity to develop mutations that may make it more dangerous to people.

“We in public health need to cast a wider net of who we offer a test,” said Shah at a press conference today. “Going forward, the CDC is expanding its testing recommendation to include workers who were exposed [to H5N1] and do not have symptoms.”

The agency is also recommending that antiviral medications be offered to asymptomatic workers who have a high-risk exposure, like those on dairy farms who may get raw milk splashed on their face. That way, if they do contract the virus, a lower amount of it will be circulating within them, which in turn lowers the risk of it spreading to other people. “The less room we give this virus to run, the fewer chances we give it to change,” said Shah.

This data also highlights that many H5N1 cases are going undetected – a concern public health officials have long suspected to be true. Yet “we can’t speculate on how many unidentified cases there may be” until we have more data, said Shah.

The CDC is now analysing an additional 150 blood samples collected from veterinarians who work with cattle. When these results become available, they should provide us with a clearer picture of how many cases may be slipping through the cracks, said Shah.