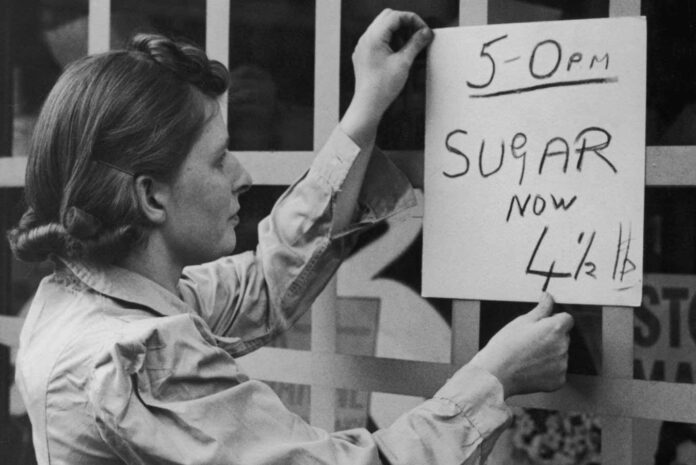

The UK was forced to ration sugar during the second world war

Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Sugar rationing during and after the second world war seems to have improved the health of people conceived in the UK at the time, cutting their risk of developing type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure decades later. This suggests that consuming less sugar in early life could boost health in adulthood.

Exposure to a high-sugar diet in the womb has previously been linked to a raised risk of obesity, which is known to increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure, or hypertension. Whether this is a causal link is unclear, however, and investigations into such questions are hampered by it being hard, or even unethical, for researchers to force people to follow specific diets.

The same isn’t true of wartime governments though, which is why Tadeja Gracner at the University of Southern California and her colleagues decided to make use of a situation in the second world war that acted like a natural diet experiment. In January 1940, a few months into the war, the UK government began rationing food. This included limiting adults to around 40 grams of sugar per day. Over a decade later, in September of 1953, rationing ended, and people rapidly increased their sugar consumption to roughly twice as much.

Gracner’s team analysed the health records of more than 38,000 people who were surveyed as part of the UK Biobank project between 2006 and 2019. All were aged between 51 and 66 at the time of the surveys and conceived within a few years before rationing ended, meaning they were exposed to limited sugar intake in the womb and early life. The researchers also looked at the same data from 22,000 people conceived a year or so after rationing ended. The two groups had a similar composition in terms of sex and race, and had a similar family history of type 2 diabetes, to enable comparisons between them.

Across both groups, there were more than 3900 people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and 19,600 were diagnosed with hypertension, but the prevalence of both conditions was much lower for those conceived during rationing. Members of this group had a 35 per cent lower chance of developing type 2 diabetes by their mid-60s, and those who did develop the condition did so on average four years later than those conceived after rationing ended. For hypertension, those in the group exposed to rationing were 20 per cent less likely to have the condition by their mid-60s, and again saw an average delay in developing it, this time of two years.

Crucially, while rationing saw many changes in the diets of people in the UK, it appears that cutting down on sugar made a big difference. Despite the changes in what food was available, average diets during rationing contained similar levels of other food types, such as fats, meat, dairy, cereal and fruit, as afterwards. One explanation might be that increased early exposure to sugar sets up a preference for eating sweet things throughout life, says Gracner. It could also lead to epigenetic changes that reduce how well people control blood sugar levels, raising the risk of type 2 diabetes and hypertension, she says.

Alternatively, it may be that generally lower calorie consumption as a result of eating less sugar could explain the improved health of those conceived during rationing, says Scott Montgomery at Örebro University in Sweden, rather than lower sugar intake per se. During rationing, people ate around 100 fewer calories a day, and people conceived during rationing had a 30 per cent lower risk of developing obesity than those conceived later, suggesting this calorie reduction played a role. “It may not be the exposure necessarily to high sugar levels, it could be something else” says Montgomery.

In any case, while the UK’s recommended dietary guidelines for sugar intake today are similar to the amount eaten during rationing, actual consumption is far higher. The results show there are clear benefits in cutting down, says Montgomery. “People should be reducing sugar intake to the recommended levels.”